A United Nations summit on the state of the world’s food systems opens today in Rome, Italy, a gathering that comes amid mounting concerns about the planet’s long-term ability to feed a fast-growing human population.

At the UN Food Systems Summit +2 Stocktaking Moment, delegates from across the planet are expected to discuss the often-devastating environmental impact of agriculture and how to make food production more sustainable.

The event is a follow-up to the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit, a landmark gathering that launched a global drive to transform the way humanity grows, processes and transports food.

To better understand what is at stake at the gathering this week, we spoke with Susan Gardner, Director of the Ecosystems Division at the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

The UN Secretary-General has said the world needs to quickly overhaul the way it produces food. What are we doing so wrong?

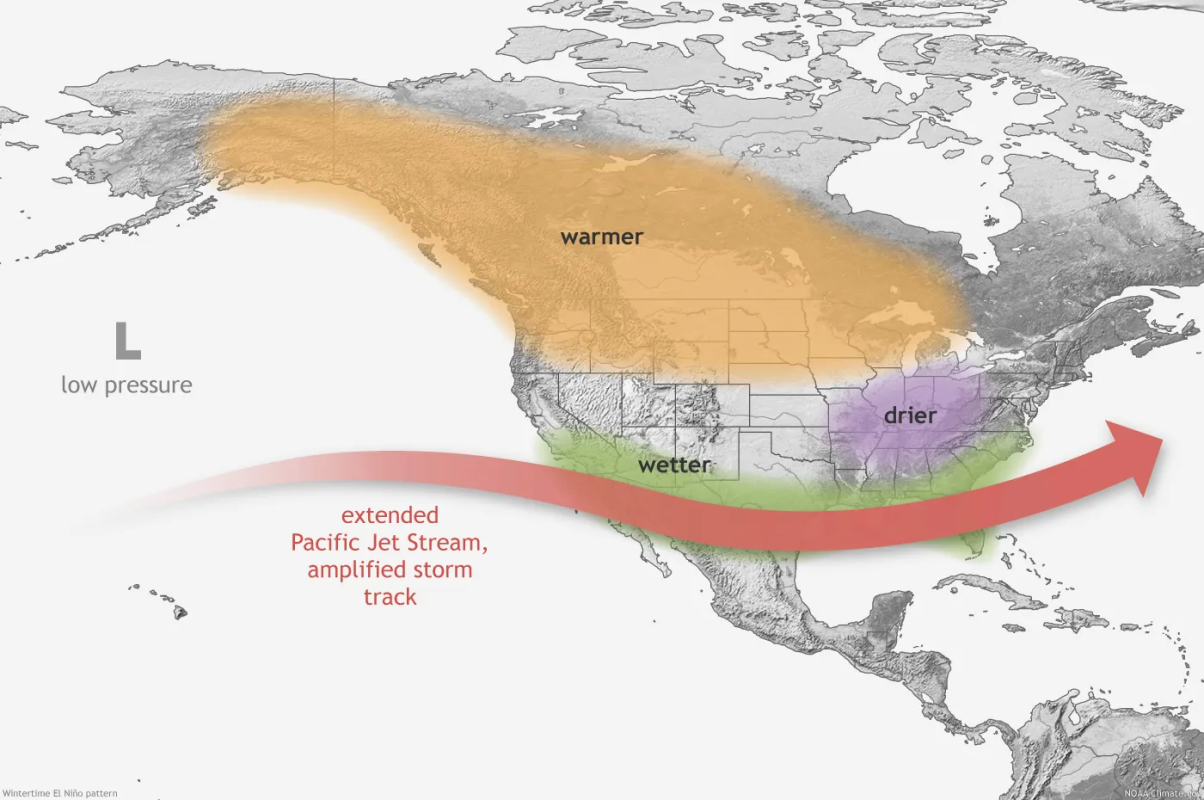

Susan Gardner (SG): Our food systems right now are unsustainable. They are a major contributor to the triple planetary crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution. For example, agriculture alone generates about one-third of greenhouse gas emissions globally. As once-wild spaces are turned into pastures and cropland, it is also responsible for over 60 per cent of biodiversity loss. To top that all off, one-third of all food produced is wasted, needlessly taxing an already stressed planet.

What are the long-term implications of all that?

SG: Food systems and nature are interlinked. Nature provides us with essential ecological services that make food production possible. That includes everything from pollination to pest control to water stability to soil fertility. We must stop nature’s decline, in order to feed ourselves in the years to come.

There are 8 billion people on this planet, hundreds of millions of whom are already hungry. Is there a danger that by making dramatic changes to our food systems we might make hunger and malnutrition worse?

SG: Changes to our food systems, when done with careful planning, can actually help alleviate hunger and malnutrition. Sustainable food systems prioritize diverse and nutritious crops, local production and farming practices that can withstand climate change. By promoting things like agroecology, regenerative agriculture and sustainable fisheries, we can increase food production while preserving ecosystems. This will reduce the risk of food scarcity and improve food security for vulnerable people.

The UN Food Systems Summit in 2021 centered on making food production less damaging to the planet. This week’s gathering in Rome will focus on the progress the world has made since then. How do you think we’re doing?

SG: There is much more work yet to be done but the signs are promising. One-quarter of countries have signaled publicly that there’s a need to reform their food systems, opening an important public discourse. And over the past two years, the UN Food Systems Task Force, co-chaired by UNEP and the World Health Organization, has helped countries begin the complicated process of reforming the way they produce food. We are seeing examples of states expanding their national development plans to include strategies for transforming their food systems. Some countries have also begun considering how changes to their food systems could impact their nationally determined contributions, the targets that are at the heart of the Paris climate change agreement.

One issue likely to come up in Rome is agricultural subsidies, which have been called damaging to the planet. How can states better spend this money?

SG: Right now, agricultural producers receive US$540 billion a year in financial support from states. The vast majority of that – some 87 per cent – either distorts prices or is harmful to nature and human health. In 2021, UNEP published a report, along with other UN partners, that called on governments to rethink the way agriculture is subsidized. By redirecting agricultural subsidies towards sustainable practices, small-scale farmers, research and innovation, rural infrastructure and nutrition, states can foster a more equitable and resilient food system.

In policy circles, there has been much talk about Indigenous food systems and how they often provide more nutrition and are easier on the planet. But how can we translate those systems, which tend to be smaller, into a global model that can feed the world?

SG: Indigenous communities hold a wealth of knowledge that can contribute greatly to our understanding of issues, such as sustainable farming techniques and seed preservation. But despite their immense cultural value, indigenous food systems are being eroded at an alarming pace. That’s because global agricultural systems are increasingly prizing just a few staple crops, specifically maize, wheat and rice. Investing in research and development specific to indigenous food systems can unlock their potential for wider application. This includes studying traditional crop varieties for their nutritional value, drought and pest resistance, and adaptation to climate change. By combining traditional wisdom with scientific advancements, we can develop crops and farming methods that are both sustainable and scalable.

The Rome meeting has been called a “make-or-break” moment for our food systems. What does a successful Stocktaking Moment look like to you?

SG: We are at a crossroads. There is no real alternative other than a strong, coordinated response to what is a deepening crisis. There are some tangible outcomes that we would like to see emerge from the discussion in Rome. Those include commitments to data-driven agricultural best practices that promote both human and ecosystem health . We’d also like to see increased support for farmers who want to transition from monocultures to more diverse and sustainable farming systems. And, we would like to see these practices integrated into national plans for agriculture, climate change and biodiversity preservation.

Are you optimistic that the world will be able to transform its food systems, especially with the clock ticking?

SG: I am. The task ahead of us is not easy. But by working collectively we can make our food systems more sustainable and resilient to climate change. That will ultimately help us make significant progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals, creating a better future for us all.

العربية

العربية